The story of Twitter’s stagnation breaks my heart a little.

Twitter managed to create a legitimately transformative product.

It did this despite the tremendous odds against any company that sets out to change the world, and pulled through early technical challenges that would have easily destroyed lesser teams.

For better or worse, Twitter’s one-to-many broadcasting mechanic and the free-form chaos of unrestricted communication offered by its “@” symbol has radically transformed the way politicians communicate with their constituencies.

It has given celebrities new and strange ways to connect with their fans and haters alike. It has shaped and altered the way people hear about and understand the news. And through all of this, Twitter has changed how hundreds of millions of human beings perceive what’s happening in their world.

And yet despite Twitter’s transformative impact, its products and the business Twitter has built around them are struggling.

Compared to the growth seen by its direct competitors (Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram), Twitter’s growth in active users is anemic:

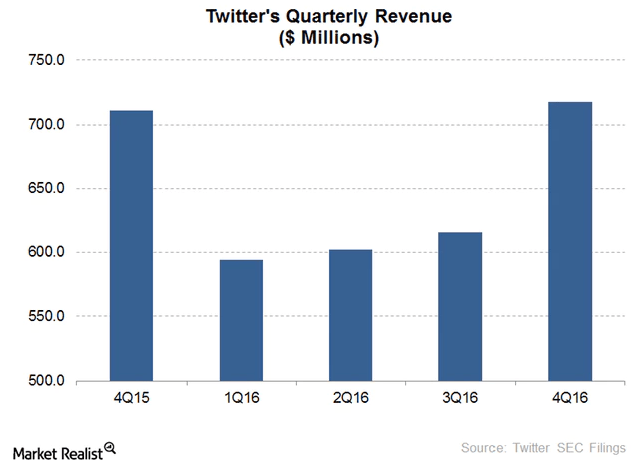

Its revenue numbers are basically flat…

Most critically, the company lost just under $457 million dollars on revenues of over $2.5 billion in 2016:

Key executives keep churning, and the leadership team’s many promises to turn things around have not turned things around.

Among those who think and write about such things, the reasons for Twitter’s stagnation are varied and wide.

They range from a lack of clear vision coming from the top to the rampant, flagrant, unchecked abuse unleashed on prominent minorities, women, and political activists by various bands of anonymous trolls, open misogynists, and proud Neo-Nazis.

The most insightful analysis I’ve seen on the subject came in a single paragraph in a big essay about consumer internet products by Arjun Sethi, an entrepreneur-turned-venture-capitalist who is now a partner at Social + Capital.

Sethi argues that every consumer internet product must go through three phases to become a lasting success: Want, need, and utility. Or, as Sethi puts it: “first you want it, then you need it, then everyone can’t live without it.”

In Sethi’s view, Twitter was on its way to becoming an essential utility and then cut itself off at the knees when it smothered its developer ecosystem by imposing severe restrictions on third party access to its APIs:

Unlike Facebook, Twitter didn’t quite make it to the utility phase of their product. Progress through the need phase was going great. The developer platform bloomed early. Developers started to use the Twitter API, building new clients and social media analytics tools. The steady decline became a reality in December 2012 after Twitter started to cut off API access to third party apps in August.

Facebook’s strategy of becoming an integral part of other company’s products was key to them becoming a utility. Twitter was on that same path prior to their limiting developer API access. The likely cause of the product not becoming a utility is the negative sentiment caused by these limits and historical lack of urgency in evolving the product for consumers.

Just for a quick refresher on the context here: In Twitter’s early days, its APIs offered third party developers nearly unmitigated access to the product’s core features.

A large number of developers used that access to build and monetize their own Twitter apps, search engines, and aggregators. Some of these products ended up becoming more compelling than Twitter’s own.

But then, in August of 2012, Twitter changed the rules. It placed a hard cap on the total number of users any third party Twitter client could have. It also added strict requirements to the functionality these apps included. And as Twitter added new features to its own web and mobile apps over the next few years, it generally did not include access to them in its APIs.

In Sethi’s view, Twitter’s decision to stifle its developer ecosystem was likely its fatal mistake, and its fate of eventual stagnation was sealed right there.

While Sethi’s excellent essay gets closer to the foundation of Twitter’s problems than any other I’ve seen, he and all the rest of the commentators are mistaking the many manifestations of Twitter’s struggles for their root cause.

Every single one of the commonly-cited reasons for Twitter’s stagnation mistakes the symptoms for the cause.

The roots of Twitter’s decline were actually established in the Summer of 2010–on the day the company’s board pushed Evan Williams out as CEO and replaced him with Dick Costolo, a man who looked at Twitter and saw a media company in the advertising business.

While the details of the events that led to that moment are fascinating and involve enough infighting, backstabbing, and subterfuge to make a Byzantine emperor proud, they aren’t relevant to this essay.

The abridged version is that between February and July of 2009, Twitter’s then-CEO Evan Williams was contemplating a massive future for Twitter, which involved growing to a billion users and becoming “the pulse of the planet.”

But just over a year later, the board pushed Williams out and replaced him with Costolo. And the new CEO’s agenda was a slightly less ambitious than his predecessor’s: put an end Twitter’s recurring downtime issues and start monetizing the product, stat.

Given that Costolo had joined Twitter from Google, and given that he’d joined Google after Google acquired the media and advertising technology company he’d co-founded, it’s perhaps not surprising that Costolo looked at Twitter in 2010 and saw a media and advertising business.

The seeds of Twitter’s stagnation were planted the day Dick Costolo decided that Twitter was a media company in the advertising business

More than any other single factor, Dick Costolo’s conclusion that Twitter was a media company in the advertising business is responsible for all of the struggles with revenue growth and profitability Twitter is experiencing today.

Because once you’re in the media and advertising business, your entire strategy–across product development, hiring, marketing, and sales–revolves around harvesting your users’ attention, maximizing their engagement, and selling pieces of that attention and engagement to advertisers.

Once harvesting attention, maximizing engagement, and selling both to advertisers become your objectives, you have tremendous incentives to consolidate your users on properties you control.

It was THESE incentives above all else that led Twitter to clamp down on third-party access to its APIs: when your main source of revenue comes from monetizing attention on your own properties, any successful third party client becomes an instant threat

But of course, while consolidating your users on your own website and apps is necessary for an ad business, it kinda defeats the point if they’re not coming back again and again. So you also must keep them engaged…very, very engaged.

For many business models built around a direct correlation between engagement and revenue, “keeping your customers engaged” often means finding ways to exploit human frailty to make your products more addicting. In others, it simply means not doing anything that alienates your most engaged users.

And while there are lots of complicated considerations concerning free speech behind Twitter’s near-complete failure to curtail the abuse on its platform, it’s also true that the trolls and automated abuse bots sure are engaged!

And lastly, any media and advertising business that wants venture-worthy returns must successfully sell the attention of its engaged users to advertisers, and do so at scale.

But ay, there’s the rub, and it’s a huge one.

Even if Twitter had managed to reach 1 billion users, it’s not clear it would ever have a meaningful competitive advantage in the ad game over Facebook and Google.

Because while it’s true that the people who buy advertising WILL PAY for the attention of engaged users, that attention by itself is NOT enough to keep those advertisers happy.

On TV, maybe.

But on the internet, where these things seem easier to measure, the people who buy advertising also want reliable returns on that investment. And while the biggest brands don’t necessarily demand that those returns come back immediately in cash, they do demand returns in the other metrics they care about: things like reach, awareness, brand lift, whatever.

And it is here, in satiating advertisers’ unending thirst for demonstrable returns, that Twitter would always be at a fundamental disadvantage to Facebook and Google.

Because even if Twitter managed to solve its user growth problems and find its way to a billion users, Facebook would still have a massive edge in targeting ads, because Facebook’s product is inherently more conducive to gathering the kind of data that makes precision ad targeting possible at scale.

And in online advertising, all the rest your base are belong to Google…because when it comes to reaching people who are ready to buy something right now, nothing beats search. And if you want to advertise to your desired audience nearly everywhere on the internet that isn’t Facebook, nothing beats Google’s Display Network.

Twitter: the pulse of the planet that never started beating.

So now we arrive at the part that breaks my heart: Evan Williams envisioned a future for Twitter as the pulse of the planet. The pursuit of this vision would almost definitely have taken Twitter down a very different path than the one it ended up taking.

Because if you’re setting out to become the pulse of the planet, your north star metric is NOT the number of active users on properties you control. It’s not about harvesting your users attention, maximizing their engagement, and monetizing both with ads.

No, if you want to be the pulse of the planet, your goal is to collect, standardize, and analyze as much data as you possibly can about anything and everything that’s happening in the world in real time.

When harvesting real time data and turning it into useful information is your goal, every successful third party app that feeds you that data is your friend. You don’t care if someone else builds a more compelling way to publish or read tweets, as long as you own those tweets.

You might not even care if someone else does a better job hosting your users photos and videos or shortening their links, as long as they give you privileged, free, and unrestricted access to any data they collect through your platform.

When you’re the pulse of the planet, don’t have to play the game of triggering dopamine releases in your users’ brains in order to harvest and monetize their attention…you’re in the business of selling access to your unique data and the extremely valuable insights contained within it.

And as Foursquare recently discovered after a long and tortuous journey trying and failing to build mainstream consumer app, the data and insights business is pretty damn good if you’ve got data people with money want and no one else has.

Indeed, there happens to be a remarkably successful private company that makes an estimated $8 billion in annual recurring revenue just selling access to its comprehensive set of real-time data and analysis tools at around $24,000 per user per year.

That company’s name is Bloomberg. And the pulse of the planet version of Twitter could have eaten Bloomberg’s core business whole.

So here’s the saddest part: When Twitter’s board ejected Evan Williams from Twitter’s CEO chair and installed a COO with a media and digital advertising background in his place, they almost definitely believed they were doing what was necessary to right the ship.

But when they pushed Williams out, they also erased Twitter’s most compelling vision of itself. They took Twitter’s big chance to become the pulse of the planet and flatlined it.

In making this choice, Twitter’s board thought they were righting the ship. Instead, they set it on a course to run aground.

And that is straight up heartbreaking.

“It was THESE incentives above all else that led Twitter to clamp down on third-party access to its APIs: when your main source of revenue comes from monetizing attention on your own properties, any successful third party client becomes an instant threat”

Can you explain this? I’m not seeing it. Don’t many other successful web services do this?

For that matter, doesn’t Facebook’s revenue comes from the same place, and isn’t Facebook your example of allowing developers better access?

Hey Tim,

Unless I’m mistaken, Facebook explicitly does not allow third party developers to replicate Facebook’s core functionality inside an app. They even shut off Flipboard’s access to the newsfeed data.

The access Facebook gives to developers generally seems designed to give developers value in exchange for making Facebook’s brand sticker/more ubiquitous and allowing it to harvest more data on its users.

That is very different from what I’m talking about here.

Maybe it will be possible to breathe some life into twitter. Especially as it is the only social entity I spend any real time on. It is deceptively simple and like so many things it makes me sad to see what it could have become.

The lack of growth in users at twitter is those who don’t really get it fading away after a few weeks.

Thanks for commenting, Neil! It’s true that new users struggle with Twitter. I’m not sure it’s as much about new users “not getting it” as it is about the way the current product is conceived and instrumented: the emotional AND practical rewards go to people with large, engaged followings.

Since the product doesn’t make it easy, simple, and fast to curate your feed at the start so the feed fills with stuff you’ll find interesting, it falls short there, too.

That was a great read, really makes sense with what is happening to Twitter.

Thanks, Guy. Glad you found it valuable…

great read!

Thanks, Deepak!

I hate it that everything always has to grow, grow, grow, or else it’s a failure. Why doesn’t it seem to be possible for a service to conclude: Ok, this is how the service is being used, and it’s good this way.

While I sympathize with this perspective, building a business around it almost inevitably leads straight to disaster.

Given that Twitter is literally losing hundreds of millions of dollars every year, “Ok, this is how the service is being used, and it’s good this way” is a one-way ticket to bankruptcy court.

But even for businesses and products that are massively profitable (especially for them!), there will always be competitors who would love nothing more than to steal your profits and take you down a peg. So unless you have a gigantic moat or some kind of regulatory or natural monopoly (like Cable/Telecom, etc) “ok, this is how the services is being used, and it’s good this way” is a surefire way to get yourself disrupted and destroyed.

Very thorough analysis (and I concur), thanks.

The acquisition of one aggregator (GNIP) and cutting off of the other (DataSift) was the point in time when I realized that an “un-platform-ization of a platform” was happening.

Totally agree, and thanks for the kind words!

Thanks for this essay, Dan! A very insightful read. As a developer, I’ve experienced the issues with the API changes you mention. I believe they really missed a big opportunity there as you suggested.

I will have to check out the rest of your series.

Glad you enjoyed it Filip!